Whoops. Thinking too much in the surf zone, Trang, Thailand.

When you are in a quickly changing situation like the political unrest in Thailand over the last few days and weeks, it pays to be flexible and responsive. We know from sea kayaking, paddle surfing and whitewater canoeing during our Expedition Field Courses at ISDSI that you need to be flexible, relaxed and aware to respond the best. When you get stiff, or freeze as you try and remember your checklist and details, is when you fail — flipping your boat, falling off, or failing to run the rapids.

Study abroad is no different.

When beginners learn a skill, they are focused on the lists — trying to remember the sequences, items, and events. With practice comes unconscious skill — you’re thinking about the movement and responding to the environment. In risk management and assessment, you need both — a list of principles that guide what you do, and the skill to apply them to fluid environments.

We’ve seen that a lot in the last few days and weeks in Thailand.

At ISDSI’s study abroad semesters in Thailand, we focus on training our American students to be culturally competent — not memorizing lists of do’s and don’ts, but rather learning Thai culture and language well enough to understand the “why” behind actions. Lists are only good for the situations you know about, but don’t necessarily guide you in what to do in new and unique situations.

At ISDSI our instructors work through lists, plans and contingencies — keeping daily course logs, training as Wilderness First Responders, working through scenarios and discussing what to do “if” — “if” being a very big, and ultimately unbounded category. However, rather than inflexible checklists or formulas, our focus is on learning how to appropriately combine three things: principles + resources + judgment.

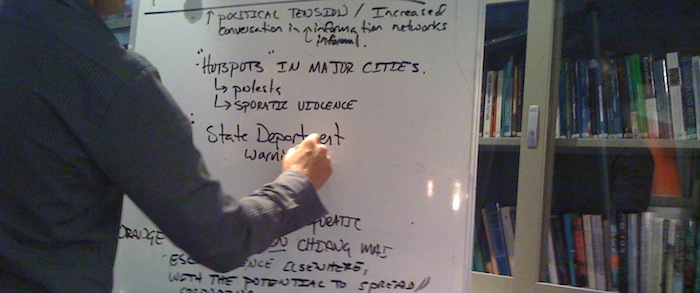

Working on the flow chart and decision tree -- it doesn't work without good judgment.

Joe Brockington, associate provost for international programs at Kalamazoo College, one of our key partners, says in “Effective Crisis Management” that a crisis is an emergency without a plan. We would add that without good judgment, skill, and experience, a plan alone is worthless — and will quickly turn into a crisis.

Faced with a situation like the protests and later riots in Bangkok, the principles of how to ensure student well-being is paramount. What resources do we have? How can we combine them in the most appropriate way? For example, the final capstone course (Coastal Ecology and Culture) had planned on having the students transit through Bangkok by train, and spend a day at the huge Chatujak Market doing a survey of coastal resources available at the market (from tropical fish to seashells). With the escalating tensions in Bangkok, we felt it would be better to avoid the city, and travel direct to the field site by bus — a decision that was easy to make, since we had the resources and experience to contact a reliable bus company, charter our own bus, and ensure that the students would arrive safely. Likewise, during the tsunami that hit Thailand, we were able to contact our students since we have lists of their mobile phone numbers, and knew where they were.

We’re hoping that things continue to calm down in Bangkok, and it looks like that is what is happening. But we don’t expect that it will be the last emergency we’ll face at ISDSI. In the meantime, we’ll continue to practice so we can be flexible and respond to the normal turbulence of living and working in Southeast Asia.

———————

For more information, see:

Effective Crisis Management by Joe Brockington.

Health, Safety, & Crisis Response by NAFSA.

The Objective Hazards of Culture outlining more of the ISDSI approach to risk management, including a list of questions for people involved in leading and managing study abroad programs.