Making the connection

How do we understand ecology and ecosystems? Not just in the classification of species or their inter-relationships, but in the “deep knowing” that one gets from a connection with the natural world?

In a classic work by the sociologist C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination, he writes about the need to be able to ask questions and pay attention to the social world:

“Method” has to do, first of all, with how to ask and answer questions with some assurance that the answers are more or less durable. “Theory” has to do, above all, with paying close attention to the words one is using, especially their degree of generality and their logical relations. The primary purpose of both is clarity of conception and economy of procedure, and most importantly just now, the release rather than the restriction of the sociological imagination. (from C. Wright Mills, The Sociological Imagination, 1959, p.178)

The methods and theory of ecology can do the same for the natural world — releasing the “ecological imagination” — connecting to and seeing the interconnections and ecological relationships of the natural world. E. O. Wilson argues that in some sense we need that connection:

[W]e are human in good part because of the particular way we affiliate with other organisms. They are the matrix in which the human mind originated and is permanently rooted, and they offer the challenge and freedom innately sought. To the extent that each person can feel like a naturalist, the old excitement of the untrammeled world will be regained. I offer this as a formula of reenchantment to invigorate poetry and myth: mysterious and little known organisms live within walking distance of where you sit. Splendor awaits in minute proportions. (Edward O. Wilson, Biophilia, 1984, p. 139, emphasis added)

Getting out into the natural world is hard to do for many students — college and university campuses are often urban or suburban, and the time to connect and be in nature is hard to find. As Richard Louv has documented in Last Child in the Woods, college students are loosing that connection that previous generations had as children. From “stranger danger” to the fears talked about on cable TV, fewer kids are let out to roam and spend time outdoors connecting.

Our society is teaching young people to avoid direct experience in nature. That lesson is delivered in schools, families, even organizations devoted to the outdoors, and codified into the legal and regulatory structures of many of our communities. Our institutions, urban/suburban design, and cultural attitudes unconsciously associate nature with doom—while disassociating the outdoors from joy and solitude. Well meaning public-school systems, media, and parents are effectively scaring children straight out of the woods and fields. In the patent-or-perish environment of higher education, we see the death of natural history as the more hands-on disciplines, such as zoology, give way to more theoretical and remunerative microbiology and genetic engineering. Rapidly advancing technologies are blurring the lines between humans, other animals, and machines. The postmodern notion that reality is only a construct—that we are what we program—suggests limitless human possibilities; but as the young spend less and less of their lives in natural surroundings, their senses narrow, physiologically and psychologically, and this reduces the richness of human experience.

Yet, at the very moment that the bond is breaking between the young and the natural world, a growing body of research links our mental, physical, and spiritual health directly to our association with nature—in positive ways. Several of these studies suggest that thoughtful exposure of youngsters to nature can even be a powerful form of therapy for attention-deficit disorders and other maladies. As one scientist puts it, we can now assume that just as children need good nutrition and adequate sleep, they may very well need contact with nature.

Reducing that deficit—healing the broken bond between our young and nature—is in our self-interest, not only because aesthetics or justice demands it, but also because our mental, physical, and spiritual health depends upon it. The health of the earth is at stake as well. How the young respond to nature, and how they raise their own children, will shape the configurations and conditions of our cities, homes—our daily lives. (From http://richardlouv.com/last-child-excerpt, emphasis added)

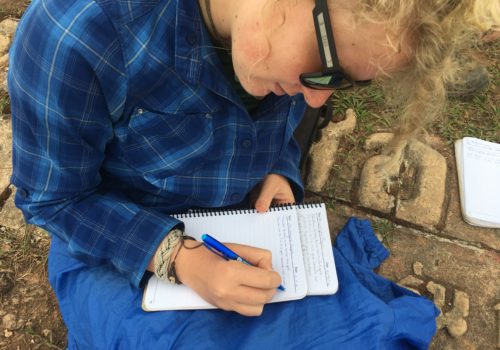

While the academic content of our courses at ISDSI is important, perhaps one of the most important and lasting things we do is allow space for students to develop their ecological imagination — seeing and knowing and understanding the connections and systems of the natural world. Giving them space and time to do this during the Expedition Field Courses is key to making the connection and reducing the nature-deficit so prevalent today. The academic content of the courses supports and broadens that connection, giving depth and meaning to what students are learning experientially. At the same time, space and time to think, reflect and write is critical if we are going to see that connection develop.

You cannot develop an ecological imagination if you’ve not spent time in the natural world.