We got back from our recon of the Yom River late Monday night for our Rivers course. It was a good chance to learn more about the river, test out our new canoes, check on gear and rigging, and see how the canoes performed in both swift water as well as some of the long shallow sections of the Yom. Not the usual prep for study abroad courses, but standard practice for ISDSI Expedition Field Courses.

Unloading the canoes for the recon.

The Yom is an interesting river. The section we paddle (about 48 km) flows through forests, and along some fields, but not through any villages or under bridges — so it has a much more “wild” feel than many rivers in Thailand. There are no weirs or dams on this section of the river, and it supports a vibrant ecological and human community — people fishing, birds hunting fish, etc. It also flows through the last remaining stand of golden teak in Thailand. The reason we paddle this section is that this is the part that will be lost if the government goes ahead with plans to dam the river (and cut the teak). So the village elders and youth activists we paddle with treasure canoeing down the river as much as we do.

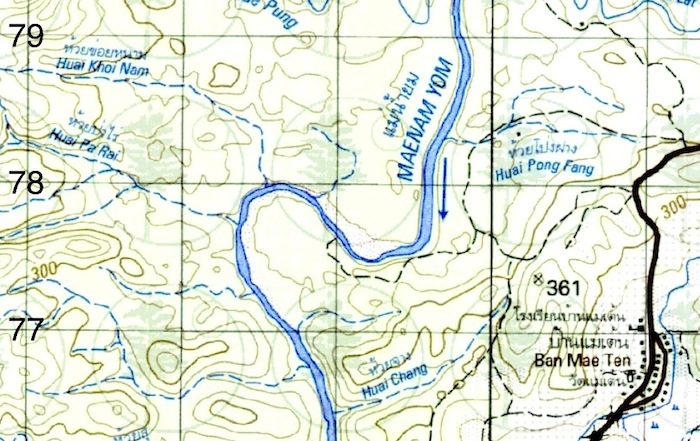

A section of the topographic maps we used. We use digitized versions we customize and print out for the course.

For the recon we had three goals. First, we needed to assess how low the river really was. The data that we had from the Thai Hydrology and Water Management Center (hydro-1.com) showed that the Yom was running at about 60 cm. Last year when we ran the river a month further into dry season, the river was running at about 80 cm. That is a pretty significant drop from last year, and we wanted to see what that meant.

The Yom river tends to have three distinct types of river topography — long and deep sections without much current, short drops with rapids (cobble stones or larger rapids), as well as sections of braided river flowing through willow thickets. Even in very dry years, the long deep sections can be paddled, but we weren’t sure about the rapids and willow thickets.

Pi Pu (with Pi Carrie in the stern) checking out the willows and reeds up close and personal...

The second reason to do the recon was to check out how the new Mad River canoes performed. We’ve used two other types of canoes in the past, PakCanoes and SOAR canoes. The PakCanoes are a skin-on-frame design, and while exceptionally lightweight, running them over rocks and rapids (especially limestone) and through willows eventually wrecked them. They are great canoes for remote wild rivers with bigger water, or lakes, but for the rough conditions we encounter didn’t really work. The SOAR canoes are amazing — they have taken the same technology for river rafts and created a two person canoe. They inflate, and are thus very easy to transport (and are, in fact, very popular in remote locations in Alaska and similar places). We used them for a few years, and then had problems with the floor welds (that kept the floor tube flat) failing. The company was fantastic, and fixed the boats for free. We’re holding on to them to use in bigger water (they are terrific whitewater boats) as well as to use if we run courses in more remote locations. In the meantime, we purchased 15 Mad River canoes (Explorer 16s).

No advanced materials for this guy's boat -- just a hewn log and hand carved paddle!

The Mad River canoes we used performed very well. The polyethylene hulls stood up to a great deal of abuse, and slid over the cobbles and river rocks (where the other canoes would have stopped). We also found that due to their hull design, you could edge the canoe (lean up on one side) and get through or over tight rocky sections. The canoes also tracked very well (were easy to keep straight) and moved very quickly in the long slack sections of the river.

Pi Noi taking a break from being office manager and dealing with paperwork to get out in the field.

The final reason we did the recon was a combination of the first two. We needed data on how fast we could expect the group to travel on each section of the river. This is a combination of the specific river topography (slack water, shallow rapids, braided willows) and the specific boats we are using (shallow “v” hulled polyethylene canoes). We used topographic maps with a 1 km UTM grid and a GPS to determine our location, and then calculated our average rate of travel for each section. That way the instructors and student leaders of the day can gauge their progress, and know when to stop, and how fast to pace themselves to accomplish the academic objectives of each day — studying the river ecology, local knowledge and community efforts to conserve the river and the fish.

Ajaan Mark and Pi Ben working out location and pace off a map and GPS (with Pi Carrie and Miriam cooling off in the background).

The recon went well. We started paddling on Saturday at 3, and started looking for a campsite as it was getting dark. The next morning, we got up early, had breakfast and broke down camp, and paddled through the day with a few rests and a lunch break. Paw Sanguan, one of the village elders, met us at lunch, and we were able to talk over the logistics for the course more, as well as how the boats handled. Paw Sanguan is expert fisherman and river paddler (in the old style dug-out canoes the villagers use as well as our new ones), and is a key instructor for our course.

We pushed hard until just before dark through lots of rock gardens, rapids, braided willow channels, and slow deep sections. We camped, ate dinner, and fell to sleep sore but happy. We were making amazing time, and would probably be able to make the take out at the Kaeng Sua Ten (Dancing Tiger Rapids) sometime the next day.

Paddling late into the day.

Up early on the river, and a cold breakfast to help with a fast start, and into our first set of rapids right away. Along the way we ran into one of the village elders (or “Paw” — meaning “father”) who was out fishing and recognized us. He figured we’d make Dancing Tiger Rapids and the national park office by mid-afternoon at our pace.

Mist on the river in the morning, with a local fisherman pulling up the night's catch just ahead of us.

We were able to push hard through some long rocky sections, and made it to a place the students will use as a campsite in time for lunch, and made a quick satellite phone call to set up our pick up. Then a couple more hours of deep slack water, and then a kilometer plus of rapids, including the Dancing Tiger Rapids. With the water level as low as it was, it involved a bit of pushing here and there, and was really technical and tricky — threading through rock gardens, and navigating the final “S” turns of the Dancing Tiger Rapid with a lot more rocks than usual (but a lot less water volume).

Ajaan Mark and Miriam (who was taking a break from Chiang Mai International School) in the midst of the Dancing Tiger Rapids.

We made it by about 3 in the afternoon — just about 48 hours total, three days, two nights.

Pi Carrie and Pi Pui pleased to be out of the willows, with a clean run down the final rapids.

We hauled gear and boats out of the river, got picked up later that afternoon, and then had a long van ride back to Chiang Mai, where we arrived late at night. The trip was great, we learned a lot about the gear, the river and the current state of the Yom. We also have enough valuable information to pass on to the instructors and students so they can make the most of their time on the river, starting on Friday, March 5th.

Each time we run the Yom, we wonder how long it will last, and how long the community can keep the river wild and undammed. Every rapid, every willow thicket, every campsite — and their home village — will all be inundated if the dam is ever built. Each run on the river helps makes their case stronger — two years ago they used photos of ISDSI students paddling the river in testimony before Thai Parliament to argue that the river was not only ecologically significant, but also internationally important — not just valuable for “only” local people (the argument of those who want to dam the river). So while our role in saving the Yom might be small, we’ll do what we can.

We’re also donating one of the Mad River Canoes to the village activist group to help them in their on-going work of studying the river and documenting its ecological significance. Paw Sanguan already is looking forward to paddling it to his favorite spots, and teaching the younger generations about the Yom.